There’s a number of things that I could’ve written about this week; the 100 minute game between France and Wales and all the biting, penalty try not giving and head injury faking that that entailed.

Or, the domination of England’s forwards by the Irish pack, or, Italy’s inability to put the ball down over the Scottish try line despite cast iron opportunities.

Instead this article will look at the restarts across in the final two games of the weekend. In each game, there was something slightly different that each team did at the kick-off. Now, this didn’t seem to be picked up in the pub I was watching the games in, but I, sat nursing a half pint of lemonade and lime and scribbling notes, found it particularly fascinating.

First of all, why do restarts matter? Well, with rugby teams gradually merging together in talent terms, the emphasis is more and more on finding those extra margins that can be gained.

The game has long since moved away from the receiving team lining up with their forwards, in scrum formation, one side and their backs the other. However, teams haven’t yet found the perfect solution to dealing with the improved abilities of the kickers.

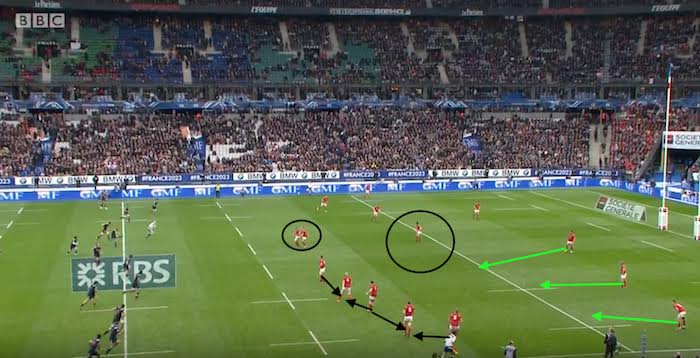

France v Wales

Wales line up with a chain of forwards towards the strong side (side with most French forwards) of the field. Ken Owens and Justin Tipuric stand directly in front of the kicker to anticipate any short balls.

The rest of the forwards, with the exception of Ross Moriarty stand in a chain with, from top of the screen to bottom; Warburton, Jake Ball, Rob Evans, Alun Wyn Jones, and, Tomas Francis. If the ball is aimed at Ball, then Warburton and Evans will lift, if it’s aimed at Alun Wyn then Francis and Evans will lift.

One other point of interest is that Leigh Halfpenny, circled, stands directly behind Tipuric and Owens to leap for any mid-length hanging kick.

The problem with this though is that if Camille Lopez could get the ball over the wall of forwards and land it on the 22, with enough hang time to allow a chaser to get there, then the Welsh backs would be taking the ball under huge pressure.

He was able to do that, and consistently target Liam Williams who got clattered as soon as he hit the floor as we see twice below.

With the area of Welsh strength so obvious, it was clear for France where they should avoid and Lopez’s kicking was good enough to land the ball on Liam Williams just slightly before the French chasers did.

France

For the French, their alignment was different; they removed the wall of forwards and put only Louis Picamoles as a jumper on the strong side. He would be able to move around to follow the ball accompanied by his two lifters located either side of him.

This reduces the sweet spot of where Dan Biggar can kick the ball to the turquoise oval. This is the spot where Picamoles can’t quite get to the ball but gets close enough that Kévin Gourdon behind hesitates and doesn’t fully go for the ball. That sounds like a tiny spot, and as you can see from the example below, it really is.

Biggar is landing the ball, if not quite on a sixpence, certainly on something no bigger than a novelty cheque. He’s doing this consistently as well, as we can see from the second example.

Unfortunately for Wales, the weakness that they exposed in France was also exposed in their own kick-off receptions. For any American Football fans, the weakness here is like the weakness in a zone defense; one zone is the wall of Welsh forwards and the other zone is the spread out players behind.

For anyone who isn’t an NFL fan, think of this as the kitchen in a flat share; you would clean your own room, but the kitchen is that place where nobody is quite committed to cleaning? The soft spot is the gap between those two, as France show below.

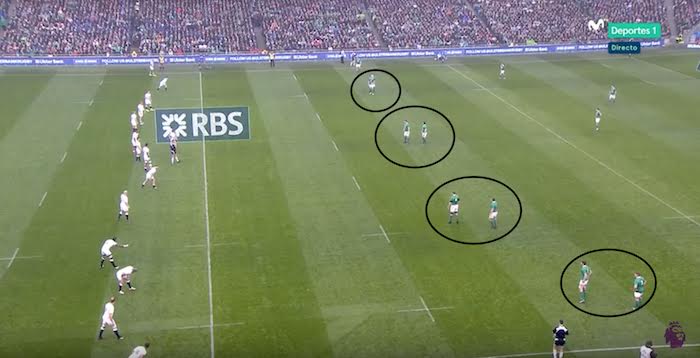

Ireland v England

Ireland’s set-up is totally different from what we see from other teams in the Six Nations. As you can see below, they spread out with their forwards in pairs between the ten and 22m lines.

They also have Garry Ringrose as a jumper, he’s being lifted by Rory Best in the shot below. The rest of the pitch is then filled out with the remaining players.

George Ford aimed for Ringrose three times during the game in an attempt to put it in the exact same gap between the zones we talked about before. From the first kick-off he missed the spot and went too long to Keith Earls.

With the second attempt he hits the spot, but Ringrose is quicker than the average forward and faster off the ground and he is able to read that the ball is going beyond him, and peel off and make the catch under minimal pressure.

In the third example, the kick is in the same direction so Best and Ringrose go back with the intention of going up for the catch. It’s too long but they act as blocker for Keith Earls who is able to catch it again, under minimal pressure.

Finally, with Ford’s kicking being perfect but the Irish restart reception working even better, England decide to kick it long for the final kick-off and allow Ireland to gather without any chasers nearby.

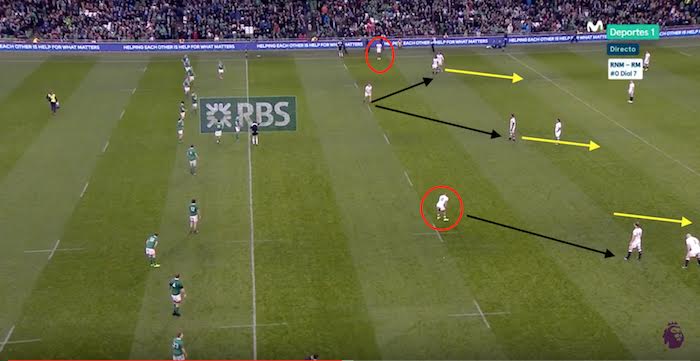

Finally, we’ll look at England. Their system is a bit of a merge between France and Ireland; they have fewer forwards in the short catching positions, like France, but they put a heavy reliance on their backs in key catching positions, like Ireland.

Anthony Watson and Jonathan Joseph (later Elliot Daly), circled in red, are responsible for the short kicks towards the sideline. They should be able to get up and claim the kicks by themselves.

Dylan Hartley, the other man on the ten-metre line, will try and lift either of the pods nearest him. Joseph will also try and lift Launchbury as well. They are much deeper than the Irish or the Welsh, reducing the space that Sexton has to kick into if he wants to win the ball back.

Because of this, the first kick is a big bomb towards Mike Brown who immediately kicks it back up the pitch.

The second kick is the same, this time a little bit shorter to invite some more pressure onto Brown, but he still has time to kick it away.

In the second half, Ireland began challenging England a little more at the restart. Sexton landed the ball on exactly the spot that we’ve spoken about previously, but Itoje is incredibly mobile and was able to get there in plenty of time.

Compare that kick with this one where Sexton switches the side he wants to kick to. Launchbury is a great player but he’s not as mobile as Itoje and so fails to cover the ground to take the ball in the air.

Jack Nowell is then caught in a difficult situation where he can’t jump into Launchbury but he doesn’t want to wait on the ground to get smashed by the Irish chasers. It’s only an Irish knock-on that prevents them stealing a bunch of metres.

Conclusion

Restarts remain an area where teams can dominate through analysis and decision making, rather than power, strength or talent. What is clear though is that you can’t cover a full half of a pitch with 15 players.

Throw men forward to cover the short kick and you increase the holes further back, move men back to cover the gap between the two zones and you leave the easy short kick as an option. The four teams we have looked at have all designed their own ways of combatting these threats. The quality of kicking is now so accurate that even the smallest of weaknesses can be found.

The invention of lifting at restarts is comparatively recent and we can expect to a number of changes coming in the next few seasons. The Irish idea of lifting backs certainly makes sense and I would expect to see more of that, after all the differences in height between backs and forwards is pretty minimal now.

We may also see teams put their three most mobile and athletic players, possibly 11,14,15, in the ten-22 metre area and move everyone else further back. That would encourage kicking teams to go short but anything slightly misjudged would result in the ball being returned at pace by someone running onto it.

One thing is for sure, the British and Irish Lions staff will be closely analysing the All Blacks’ restarts to try and find a way of gaining an upper hand in this part of the game.

By Sam Larner , Courtesy:Planet Rugby